КУЛЬТУРА УКРАЇНСЬКОГО

НАУКОВОГО ТЕКСТУ

1. Науковий текст

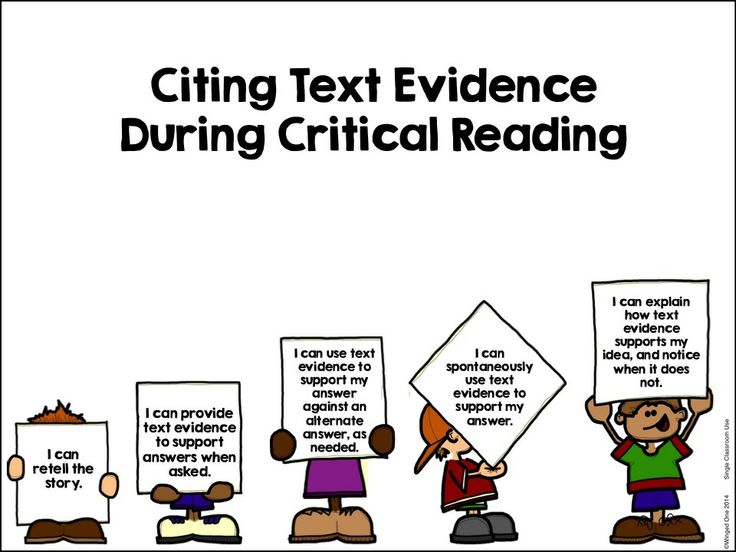

2. Культура особистості дослідника

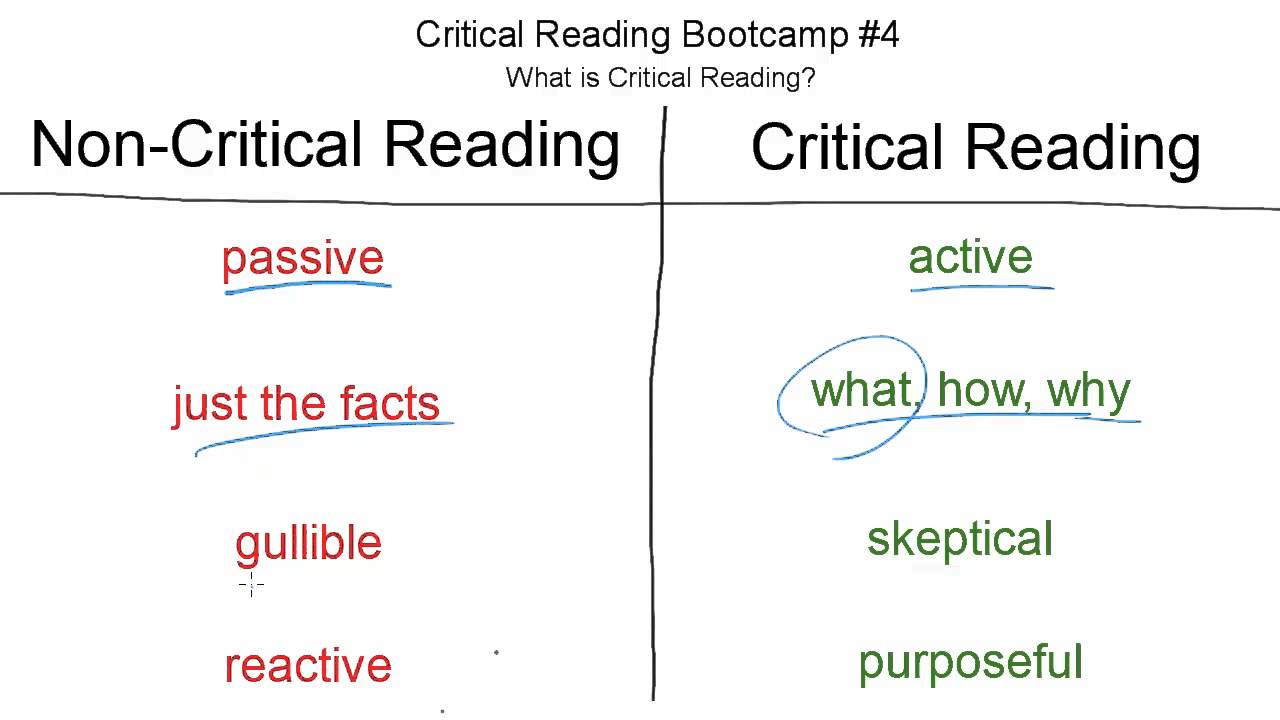

3. Культура читання наукового тексту

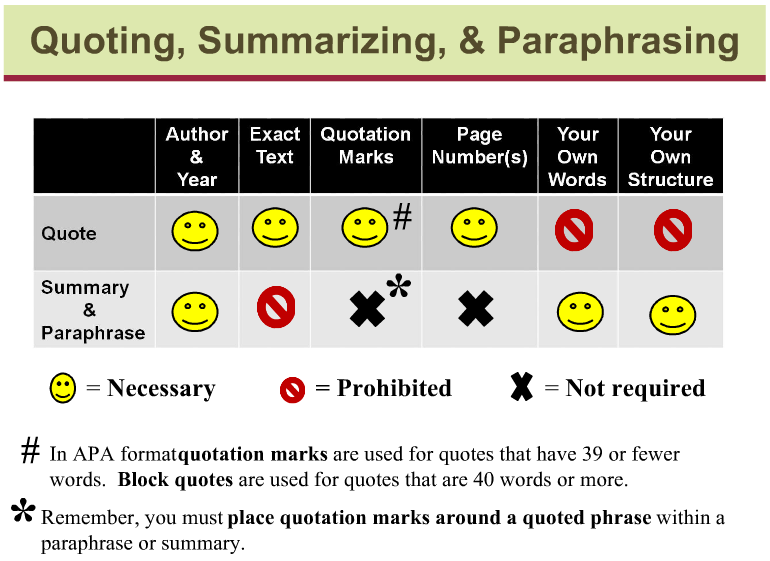

4. Компресія наукового тексту

5. Композиція наукового тексту

6. Наукова стаття як самостійний науковий твір

7. Мова і стиль кваліфікаційної роботи

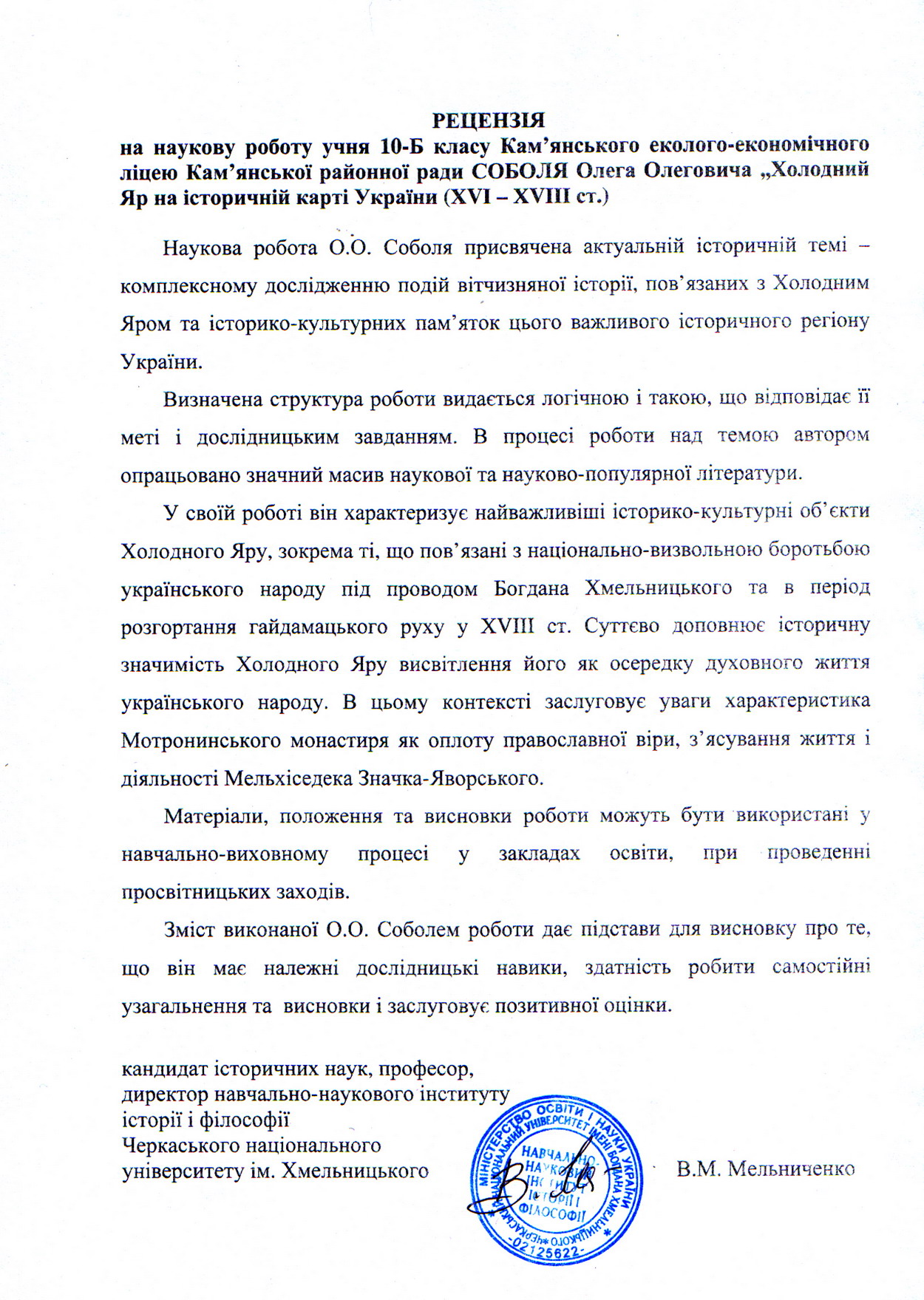

8. Науковий відгук і наукова рецензія

НАУКОВОГО ТЕКСТУ

1. Науковий текст

2. Культура особистості дослідника

3. Культура читання наукового тексту

4. Компресія наукового тексту

5. Композиція наукового тексту

6. Наукова стаття як самостійний науковий твір

7. Мова і стиль кваліфікаційної роботи

8. Науковий відгук і наукова рецензія